Top tips:

-

- Pain is a complex symptom and requires consideration of many factors for diagnosis and management. This guidance will focus on chronic pain (>3 months).

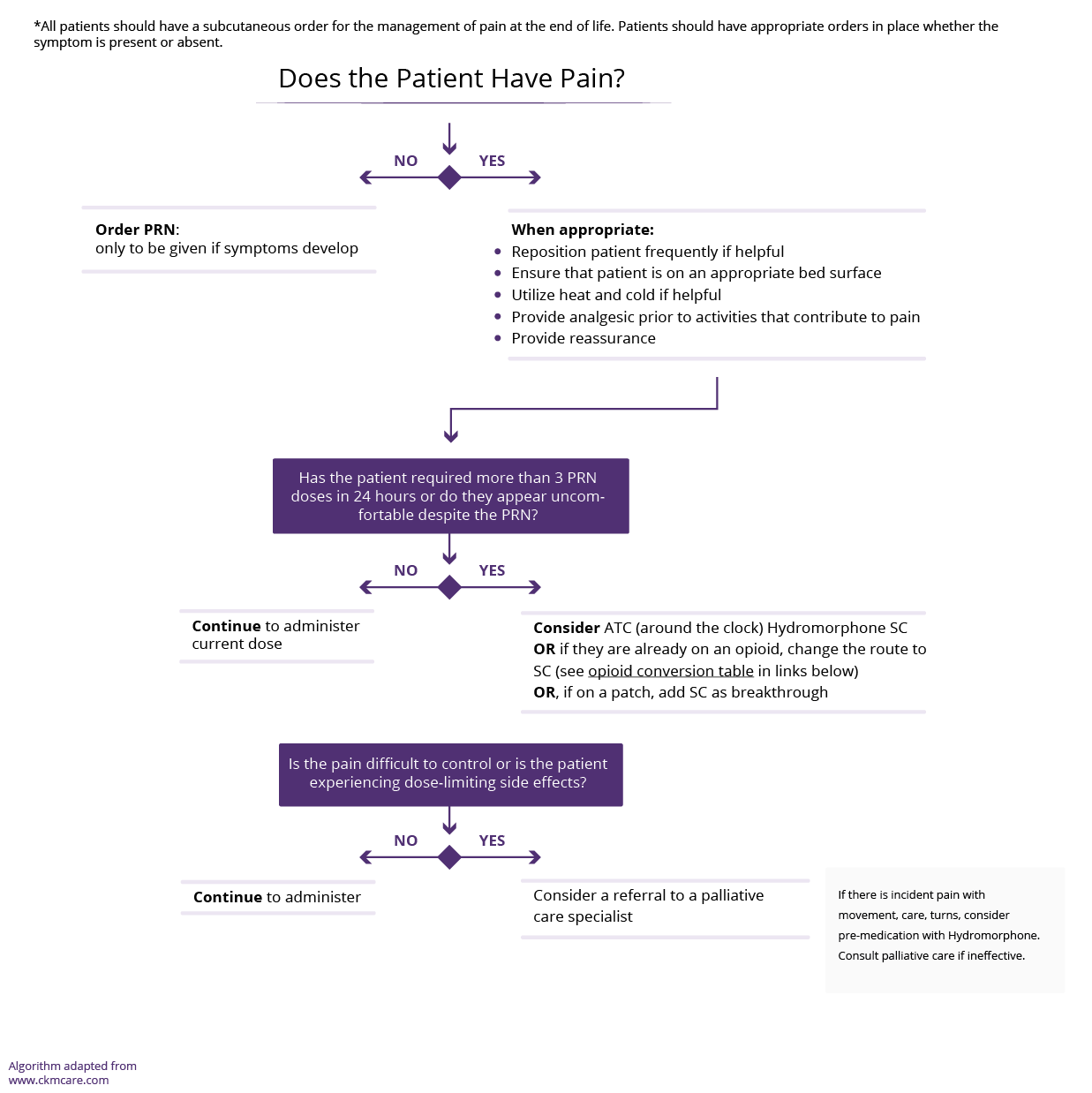

- A separate algorithm is provided for pain at end-of-life (last days/weeks of life).

- Separate tips are provided for acute pain management in the hospital setting.

- A thorough assessment of pain requires the following three things:

- Quantify pain and its impact using a standardized pain assessment tool

- Consider psychosocial contributors to pain and look for co-existing mental health conditions

- Addiction risk assessment

- Set realistic expectations for pain relief, in chronic pain focusing on function and goals rather than complete resolution. In general, the most that can be expected from outpatient drug treatment for chronic pain is a 30-50% reduction in intensity. Prepare the patient that the medication will be discontinued if desired effect is not achieved.

- Consider non-pharmacological therapies in all patients

- Consider the type of pain when prescribing pharmacological therapies

- Opioids are important agents in the correct setting. They should be used with caution in cirrhosis as they can worsen hepatic encephalopathy and increase risk of falls. If needed for pain management, adjust doses and dosing interval to the degree of hepatic dysfunction

- Regularly reassess the pain after initiation of pharmacological therapy to determine need for ongoing therapy

- At end-of-life, the risk-benefit ratio of pharmacological therapy may change and patients may be more accepting of sedation.

Is the pain acute with an identifiable non-cirrhosis or cirrhosis related acute cause that can be treated (e.g. a hip fracture after a fall, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, increasing ascites contributing to abdominal distension). Treat the cause. This guidance statement does not apply to acute pain.

Is the pain chronic (present for >3 months). Consider the differential diagnosis. Modify what is modifiable if this is in keeping with the patient’s goals of care.

Pain is a complex multidimensional experience with biopsychosocial inputs. Depending upon the situation, assess the following three things as part of a thorough pain assessment:

Use one of the following standardized pain assessment tools to evaluate pain and monitor the effectiveness of pain management.

- PEG 3-Item Scale (Pain, Enjoyment and General Activity scale) Adapted from the brief pain inventory, assesses pain intensity and interference

- ESAS-r pain rating

- More detailed tool: AHS Initial Pain Assessment Tool

Consider psychosocial contributors and screen for co-existing mental health conditions as these will affect the pain experience:

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Others (Post-traumatic stress disorder, psychosis)

Ask about alcohol and other substance use as this may affect your management decisions.

- Links to structured screens:

- Alcohol use disorder: AUDIT-C (3 questions)

- Drug misuse screening: DAST-10 (10 questions)

Screen for opioid risk:

Consider Non-pharmacological therapies

Consider non-pharmacological management in all patients in addition to pharmacological therapies.

Analgesics and other drugs are only a partial solution to the management of pain in cirrhosis (see Chronic Pain Tips).

These may have varying uptake and utility for each person and should be suggested on a case-by-case basis. Common examples:

-

- Exercise

- Mind-body practices (e.g. meditation/yoga)

- Counselling

It is important to consider the type of pain the patient is experiencing – main consideration:

Nociceptive (somatic/visceral pain) versus Neuropathic (nervous system pain,“burning/electrical”)

- Reassess pain at least monthly using the PEG, ESAS-r or the Follow-up Pain Assessment Tool to determine if there is benefit to current medication.

- If the pain is not responding as expected, go back to your differential diagnosis, re-assess for non-physical contributors to pain and review expectations for pain relief.

- Pain adequately controlled – Continue to reassess monthly

- Pain somewhat controlled but inadequate – Continue first line medication and add second line medication

- Pain not controlled (no benefit) – Stop first-line medication and start second line medication

- The dose of medications may need to be adjusted with deteriorating liver function.

Nociceptive pain arises from damage or injury to nociceptors and encompasses both somatic (soft tissue, bone, joints) and visceral pain (from vital organs). This is often the most common type of pain.

Localized pain may respond to local treatment. For non-localized chronic pain, acetaminophen is recommended as first-line.

| Medication: | Recommended Dose | Additional information |

|---|---|---|

|

Acetaminophen |

325-1000 mg PO q6-12 h/day |

First line Dose reduce to a maximum of 2 grams per day if needed regularly, long-term |

|

Diclofenac gel |

5% or 10% gel applied topically BID or TID. Over the counter products are 1.16% and 2.23%. |

First line for localized joint pain |

| REASSESS PAIN AT LEAST MONTHLY - If above therapies are ineffective and pain is significantly impacting quality of life AND function, weigh the risks and benefits of opioid therapy | ||

Neuropathic pain arises from structural or functional derangement of the tissues of the nervous system itself. Adjectives like burning or electrical may indicate neuropathic pain.

True neuropathic pain is uncommon. Gabapentin and pregabalin have the potential for misuse. Avoid prescribing these for pain unless you can make a clear diagnosis of neuropathic pain (see Chronic pain tips ).

| Medication: | Recommended Dose | Additional information |

|---|---|---|

| (Before use, see the product monograph for complete side effect list) | ||

|

Gabapentin |

100 mg PO qhs. |

First line |

|

Pregabalin |

25-50 mg PO qhs |

Alternate First line |

|

Acetaminophen |

325-1000 mg PO q6-12 h/day |

Second line |

|

REASSESS PAIN AT LEAST MONTHLY - If above therapies are ineffective and pain is significantly impacting quality of life AND function, weigh the risks and benefits of opioid therapy |

||

- The risks and benefits of opioid medications need to be very carefully weighed in all patients, but particularly in those patients with cirrhosis.

- Consider opioids only in patients who have failed non-opioid therapies and have refractory pain that is significantly impacting quality of life and function

- Unless the practitioner is very experienced, assistance should be sought before using opioids in the following situations:

-

- Contributing psychosocial determinants or untreated mental health disorders (see Total Pain Syndrome under Chronic Pain Tips)

- High addiction risk (Opioid risk tool revised Link)

- Uncontrolled hepatic encephalopathy (see CCAB HE page)

-Patients meeting these criteria often benefit from consultation with an inter-disciplinary Pain Clinic (earlier stages of cirrhosis), palliative care (end-of-life), hepatology (uncontrolled hepatic encephalopathy).

-If clinic wait lists are too long or rapid assistance is required, in Alberta, these specialists can be reached through RAAPID North (780-735-0811) or RAAPID South (403-944-4486).

- The use of opioids in people with more advanced liver disease has implications around pharmacokinetics and stigmatization around people who may be living with opioid use disorder. This requires careful attention to addressing opioid myths and monitoring for opioid toxicity (Guideline for treatment of opioid neurotoxicity).

- Review the results of the opioid risk tool revised. If the patient is at risk, suboxone (buprenorphine/naloxone) is recommended as the drug of choice, unless the prescriber has specific training in Addiction Medicine

- Educate the patient about expected side effects

- Review the patient’s Personal Pain Goal (numerical pain intensity they can function in the capacity they are best able, see general approach to symptom assessment box at top of page), in addition to goals for increased function and quality of life. Reinforce that in a best-case scenario, pain typically decreases by 30-50%

- Start low doses and titrate up slowly to the lowest effective dose

- Do not initiate long-acting formulations in patients with cirrhosis

- In physically or cognitively frail patients, some experts start with a single dose of an opioid at qhs to assess tolerance, and to add doses from there

- All opioids are associated with a risk of constipation and worsening hepatic encephalopathy.

- Order a bowel routine (see Constipation page) and for the first 3-5 days of therapy (or dose changes), order prn anti-nauseants (see Nausea page).

- Consider Home Care involvement if the patient is unable to take their own medications

If using opioids, ensure that you monitor for the signs of opioid toxicity and ensure timely management of this. Guidance on opioid induced neurotoxicity can be found here

| Medication: | Recommended Dose | Additional information |

|---|---|---|

| (Before use, see the product monograph for complete side effect list) | ||

|

Hydromorphone (immediate release) |

Oral: 0.5 or 1 mg PO q 4 or q6h Max: Titrate up as required/tolerated |

First line (in all). |

|

Morphine sulphate |

2.5mg PO q4 or q6h Max: Titrate up as required/tolerated |

The AASLD 2022 guidance statement recommends against morphine use. This is based on expert consensus, and in clinical practice, alternatives may be |

|

Buprenophine/Naloxone (Suboxone) |

Starting: 4 mg SL once daily |

First line if history of substance use disorder |

AVOID

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

-

- Increases the risk of renal dysfunction and bleeding

Demerol

-

- Build-up of toxic metabolites.

USE WITH CAUTION

Codeine

-

- Pro-drug that requires conversion to morphine in the liver. Results in variable analgesia as liver dysfunction progresses.

- Clearance can also be slowed, resulting in depressed ventilation. If used, start with lower doses and longer dosing intervals (15-30 mg PO tid), followed by careful titration. AVOID in Child Pugh C disease.

Oxycodone

-

- Relies on CYP metabolism to its active metabolite. Unpredictable levels. No subcutaneous alternative for end-of-life.

Fentanyl transdermal patch

-

- Do not use in opioid naïve patients

- Avoid in “severe hepatic impairment”

- Consult pain management specialist or if the patient is end-of-life, a palliative specialist

Tramadol/Tramacet

-

- Requires activation by hepatic oxidation so effects may be less predictable with hepatic dysfunction. Avoid in Child Pugh C disease.

- Lowers the seizure threshold.

- Metabolism decreases with progression of liver disease, reducing the analgesic effect.

- Be aware that Tramacet contains acetaminophen (daily total limit of acetaminophen is 2-3g over 24h)

- The British Association for the Study of the Liver guidance recommends against use in cirrhosis

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

-

- Increases the risk of renal dysfunction and bleeding

Demerol

-

- Build-up of toxic metabolites.

USE WITH CAUTION

- Ongoing pain reassessment (q 2-4 weeks) is critical (PEG, ESAS-r, Follow-up pain assessment tool)

- Uncontrolled pain is defined as >3 breakthrough doses per day for 3 consecutive days

- Most medications targeting neuropathic pain are not available as injectables when subcutaneous route needed (eg. gabapentin). A switch to opioid medication will likely be necessary.

- Given the focus on comfort, CNS side effects are often not as critical for patients. Good discussions are important. Faster titration of medications may result in more CNS depressant effects, which may be aligned with patient goals.

- Patients usually require subcutaneous medications at the end of life when they lose the ability to swallow.

- A history of substance use may affect the dosing of medications required at the end-of-life and may make the patient and family more reluctant to use opioids. Specialist consultation may be required.

- Pain management remains suboptimal despite above approach.

- An opinion about safety and limits of therapy is needed.

- Assistance with management of Total Pain Syndrome is needed.

- Tertiary palliative care unit or Hospice placement is required (Palliative Care specialist, may be regional variation).

- Practitioner uncertain regarding any of the above steps.

- Multi-symptom complexity, including pain.

- Patient or family psychosocial distress compounding the pain experience.

- Complex advance care planning in combination with pain.

This section was adapted from content using the following evidence based resources in combination with expert consensus. The presented information is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of physicians or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient’s care.

Authors (Alphabetical): Amanda Brisebois, Sarah Burton-Macleod, Ingrid DeKock , Martin Labrie, Noush Mirhosseini, Mino Mitri, Kinjal Patel, Saifee Rashiq, Aynharan Sinnarajah, Puneeta Tandon

Thank you to pharmacists Omer Ghutmy and Meghan Mior for their help with reviewing these pages.

Helpful links:

- General approach to pain: Chronic Pain Tips

- Substance use: https://crismprairies.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Guidance-Document-FINAL.pdf

- Fraser Health Symptom tools: https://www.fraserhealth.ca/-/media/Project/FraserHealth/FraserHealth/Health-Professionals/Professionals-Resources/Hospice-palliative-care/SymptomAssessmentRevised_Sept09.pdf

- Excellent reference for opioid prescribing for chronic non-cancer pain – Busse JW et al. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170363

- Alcohol use disorder: AUDIT-C (3 questions)

- Drug misuse screening: DAST-10 (10 questions)

- Opioid Risk Tool-revised

References:

- Alberta Health Services. Seniors Health, Palliative and End of Life Care. Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Neurotoxicity; Available from: Alberta Health Services

- Davison SN on behalf of the Kidney Supportive Care Research Group. Conservative Kidney Management Pathway; Available from: https//:www.CKMcare.com.

- British Association for the Study of the Liver. Clinical Guideline. Symptom Control and End-of-Life care in adults with Advanced Liver Disease. Version 1.0.

- Bosilkovska M, Walder B, Besson M, Daali Y, Desmeules J. Analgesics in patients with hepatic impairment: pharmacology and clinical implications. Drugs. 2012 Aug 20;72(12):1645-69. doi: 10.2165/11635500-000000000-00000. PMID: 22867045.

- Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, Buckley DN, Wang L, Couban RJ, Agoritsas T, Akl EA, Carrasco-Labra A, Cooper L, Cull C, da Costa BR, Frank JW, Grant G, Iorio A, Persaud N, Stern S, Tugwell P, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2017 May 8;189(18):E659-E666. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170363. PMID: 28483845; PMCID: PMC5422149.

- Chandok N, Watt KD. Pain management in the cirrhotic patient: the clinical challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 May;85(5):451-8. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0534. Epub 2010 Mar 31. PMID: 20357277; PMCID: PMC2861975.

- Imani F, Motavaf M, Safari S, Alavian SM. The therapeutic use of analgesics in patients with liver cirrhosis: a literature review and evidence-based recommendations. Hepat Mon. 2014 Oct 11;14(10):e23539. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.23539. PMID: 25477978; PMCID: PMC4250965.

- Klinge M, Coppler T, Liebschutz JM, Dugum M, Wassan A, DiMartini A, Rogal S. The assessment and management of pain in cirrhosis. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2018 Mar;17(1):42-51. doi: 10.1007/s11901-018-0389-7. Epub 2018 Feb 22. PMID: 29552453; PMCID: PMC5849403.

- Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, Damush TM et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. Journal of general internal medicine 2009 Jun 1;24 (6):733-8. PMID 19418100.

- Lewis JH, Stine JG. Review article: prescribing medications in patients with cirrhosis – a practical guide. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Jun;37(12):1132-56. doi: 10.1111/apt.12324. Epub 2013 May 3. PMID: 23638982.

- Moulin D, Boulanger A, Clark AJ, Clarke H, Dao T, Finley GA, Furlan A, Gilron I, Gordon A, Morley-Forster PK, Sessle BJ, Squire P, Stinson J, Taenzer P, Velly A, Ware MA, Weinberg EL, Williamson OD; Canadian Pain Society. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain: revised consensus statement from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manag. 2014 Nov-Dec;19(6):328-35. doi: 10.1155/2014/754693. PMID: 25479151; PMCID: PMC4273712.

- Murphy EJ. Acute pain management pharmacology for the patient with concurrent renal or hepatic disease. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2005 Jun;33(3):311-22. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0503300306. PMID: 15973913.

- Rakoski M, Goyal P, Spencer-Safier M, Weissman J, Mohr G, Volk M. Pain management in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2018 Jul 26;11(6):135-140. doi: 10.1002/cld.711. PMID: 30992804; PMCID: PMC6385960.

- Rogal SS, Winger D, Bielefeldt K, Szigethy E. Pain and opioid use in chronic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2013 Oct;58(10):2976-85. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2638-5. Epub 2013 Mar 20. PMID: 23512406; PMCID: PMC3751995.

- Schweighardt AE, Juba KM. A Systematic Review of the Evidence Behind Use of Reduced Doses of Acetaminophen in Chronic Liver Disease. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2018 Dec;32(4):226-239. doi: 10.1080/15360288.2019.1611692. Epub 2019 Jun 17. PMID: 31206302.

Last reviewed July 3, 2024.