Top tips:

- Nausea and vomiting are less common than other GI symptoms in cirrhosis however can be experienced in a significant number of patients

- Nausea originates from GI or CNS receptor stimulation

- Always rule out constipation and dehydration and treat them if they are present

- Be aware that nausea and vomiting can impact nutritional intake

Check out the bottom of the page for short videos from Dr. Sarah Burton-Macleod!

The more common causes of nausea in this population include the following:

- Constipation

- Ascites

- Medications e.g. opioids, SSRI antidepressants, antidiabetic meds, beta-blockers, etc.

- llicit substances

- Gastroparesis/ileus

- Acute GI infections (eg gastroenteritis), or other infections

- Non-pharmacological measures should be considered in all patients where the symptom is having a significant impact on quality of life or ability to function.

- Nutritional intake may be impacted by chronic nausea and vomiting (see Nutrition page CCAB)

- Provide patients with the Nausea/Vomiting Patient handout (link after developed).

- Avoid constipation (LINK to CCAB Constipation page)

- Encourage good oral hygiene

- Eater smaller amounts of food slowly and more frequently

- Drink fluids 30-60 mins prior to meals

- Avoid foods that are greasy, spicy, or excessively sweet

- Do not drink alcohol

- Minimize triggering aromas (cooking odours, perfumes, smoke, etc)

- Suggest loose fitting clothing

- Apply a cool, damp cloth to the forehead or nape of neck

- Relaxation, acupressure or acupuncture

- Ginger has been shown to be a promising therapy across clinical studies though the target dose remains unclear. Tablets or real ginger can be used.

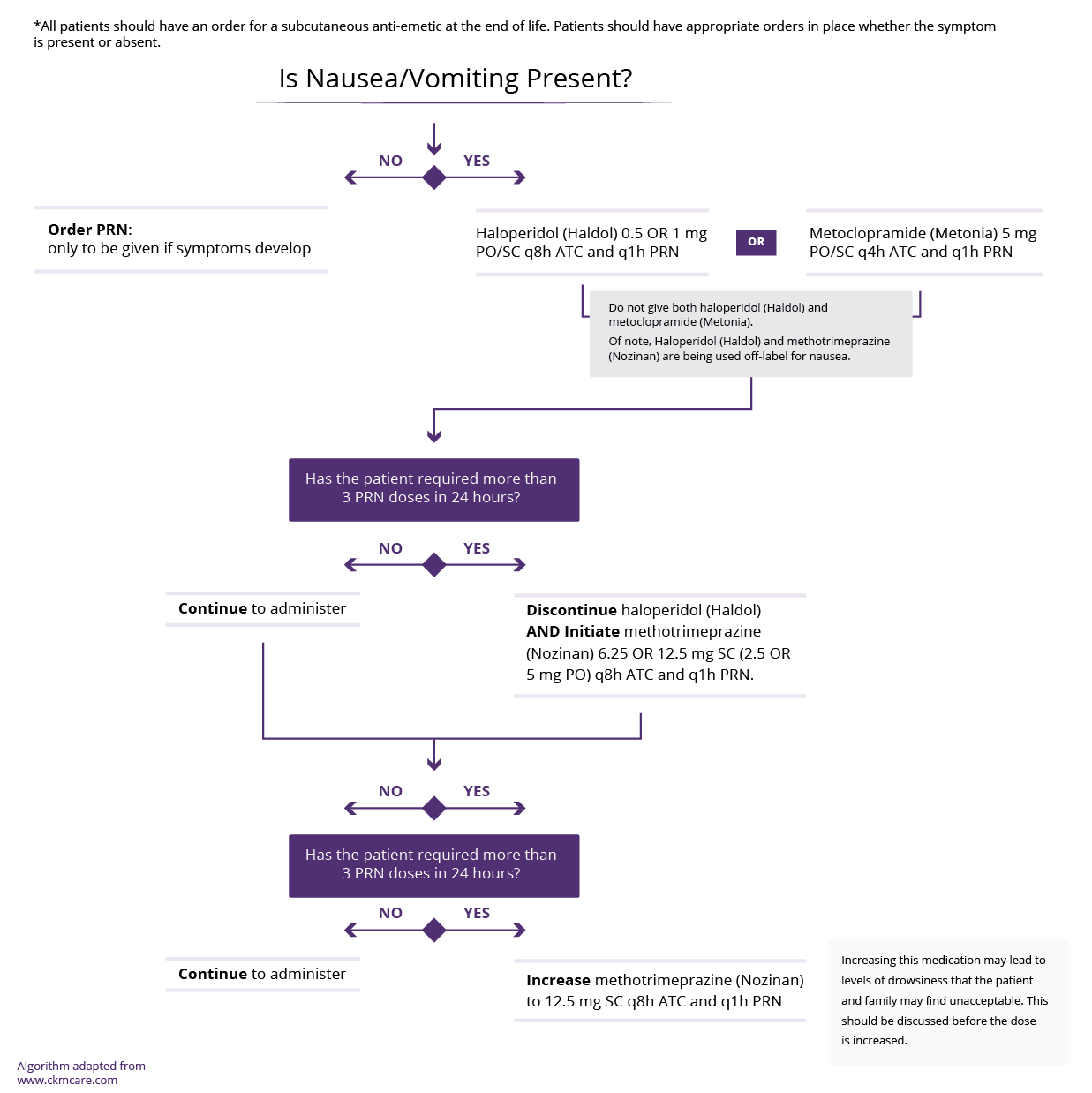

These medications should be considered in patients with chronic, persistent nausea.

The primary goal of therapy is to balance symptom control with the careful protection of physical function and cognition. Be aware that many anti-nausea medications can cause QTc prolongation.

When choosing an anti-emetic consider the following:

- Etiology of the nausea (GI versus opioid/centrally induced).

- Side effect profile, choosing the medication that won’t worsen already present conditions (such as constipation, QTC prolongation)

- Cost

Use only ONE of below medications at a time (stop if ineffective, and progress to next line medication).

| Medication: | Recommended Dose | Additional information |

|---|---|---|

| (Before use, see the product monograph for a complete side effect list) | ||

|

Metoclopramide |

5 OR 10 mg PO/SC q6h ATC (often given before meals and Qhs)

|

First line for GI cause.

Child Pugh B/C max dose 20 mg/day.

|

|

Domperidone |

10 mg PO TID |

First line for GI cause, particularly in ambulatory patients with intermittent nausea.

|

|

Haloperidol |

0.5 mg PO/SC q8h ATC and 0.5 mg PO/SC q1 h PRN In severe, persistent nausea use BID ATC and q4h PRN |

First line for opioid induced/centrally induced nausea.

|

|

Ondansetron |

4 mg PO q4h PRN

|

Second line for post-surgical or centrally /medication induced nausea (e.g.) chemotherapy.

|

|

Olanzapine |

2.5 mg PO q4h PRN

|

Second line

|

|

Dimenhydrinate |

25-50 mg PO q4h PRN

|

Third line

|

This section was adapted from content using the following evidence based resources in combination with expert consensus. The presented information is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of physicians or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient’s care.

Authors (Alphabetical): Amanda Brisebois, Sarah Burton-Macleod, Ingrid DeKock , Martin Labrie, Noush Mirhosseini, Mino Mitri, Kinjal Patel, Aynharan Sinnarajah, Puneeta Tandon

Thank you to pharmacists Omer Ghutmy and Meghan Mior for their help with reviewing these pages.

Helpful links:

- Alberta Health Services Goals of care

- Constipation: http://cirrhosiscare.ca/symptom-management-provider/constipation-diarrhea-hcp/

References:

- Davison SN on behalf of the Kidney Supportive Care Research Group. Conservative Kidney Management Pathway; Available from: https//:www.CKMcare.com

- Glare P, Miller J, Nikolova T, Tickoo R. Treating nausea and vomiting in palliative care: a review. Clin Interv Aging. 2011;6:243-59. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S13109. Epub 2011 Sep 12. PMID: 21966219; PMCID: PMC3180521.

- Marx W, Kiss N, Isenring L. Is ginger beneficial for nausea and vomiting? An update of the literature. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015 Jun;9(2):189-95. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000135. PMID: 25872115.

- Palliative care and end-stage liver disease ; 2019; Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 35(3):155-16. PMID: 30925536.

- Peng JK, Hepgul N, Higginson IJ, Gao W. Symptom prevalence and quality of life of patients with end-stage liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med. 2019 Jan;33(1):24-36. doi: 10.1177/0269216318807051. Epub 2018 Oct 22. PMID: 30345878; PMCID: PMC6291907.