Top tips:

- Sleep disturbances occur in 27-70% of patients with cirrhosis

- Hepatic encephalopathy must be considered in any patient with cirrhosis and excessive daytime sleepiness

- Treat if sleep disturbances are impacting the patient’s quality of life and daily functioning

- Consider non-pharmacological interventions before pharmacological therapy

- At the end of life (last few days or weeks), sleepiness may increase due to disease progression (and/or medications)

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is the diagnosis of exclusion in any patient with cirrhosis and excessive daytime sleepiness. In patients with cirrhosis and HE, studies of lactulose or rifaximin have demonstrated improved sleep. See HE page for treatment of suspected HE.

These tools assess difficulty falling and/or staying asleep, or daytime sleepiness

-

- Sleep Timing and Sleep Quality Screening Questionnaire takes 2 minutes to complete

Sleep Timing and Sleep Quality Screening Questionnaire - Epworth Sleepiness Scale measures excessive daytime sleepiness – score of ≥ 11 is abnormal

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- Sleep Timing and Sleep Quality Screening Questionnaire takes 2 minutes to complete

-

- Cirrhosis complications – e.g., ascites, muscle cramps, pruritus, pain, breathlessness

- Medications/toxins – e.g., diuretics, alcohol use

- Other acute or chronic comorbidities – e.g., obstructive sleep apnea, mood disorders – anxiety/depression, cognitive impairment

Consider non-pharmacological management in all patients where sleep disturbance is having a significant impact on the patient’s quality of life and ability to function.

- Wake up at the same time every morning

- Do not go to bed until you feel sleepy

- Develop a relaxing bedtime ritual such as taking a warm shower or reading something relaxing before going to bed

- Do not “try” to fall asleep

- Avoid napping during the day

- Avoid caffeine and nicotine in the evening

- Avoid treating sleep problems with alcohol

- Exercise early in the day. Avoid exercising before bed as this may keep you up at night

- Save your bedroom for sleep (and sex) only

- Don’t watch television or use mobile phones, tablets or computers in bed as these activate your brain

- Keep bedroom dark and cool at night

- If you have gone to bed and are unable to sleep, get out of bed and do something relaxing before returning to bed

- Cognitive and psychological therapies such as mindfulness: evidence supports 4-weeks of mindfulness and supportive group therapy to improve sleep quality and reduce depression scores

- Bright-light therapy: to date there are inadequate studies in cirrhosis, but this treatment is promising. Promote bright light exposure in the early hours of the morning and bright light avoidance, including light that comes from mobile phones, tablets or computers in the evening

- Be VERY cautious of using pharmacological interventions, as they increase risks of cognitive dysfunction and falls especially if daytime sleepiness is already present

- Use the sleep assessment tools to reassess the effectiveness of medications 2-4 weeks after prescription

- Avoid over the counter sleep aids, and benzodiazepines if possible

There is limited evidence for the pharmacological management of sleep disturbances in cirrhosis. Small randomized controlled trials are available for the use of Zolpidem and for Melatonin.

| Medication: | Recommended Dose | Additional information |

|---|---|---|

|

Zolpidem |

5mg PO qhs for SHORT term use (<2weeks) |

Limited Evidence - 4-week RCT (Sharma 2019) in Child Pugh A/B patients showed increased sleep time and sleep efficiency |

|

Melatonin |

3mg PO/SL qhs |

Limited Evidence 2 week RCT (De Silva 2020) in Child Pugh A/B patients showed increased sleep quality and decreased daytime sleepiness |

|

Hydroxyzine |

AALSD additionally recommends use of hydroxyzine 25mg qhs but this has limited evidence for use. |

Formal studies are required to establish the risks and benefits of these medications in cirrhosis.

If this Expert opinion based medications is used, it should only be used short term unless the patient is in their last few months of life when symptom control is the priority.

| Medication: | Recommended Dose | Additional information |

|---|---|---|

|

Zopiclone |

3.75-5mg PO qhs |

Limited Evidence Based on expert opinion only - In non-cirrhosis patients, this can be helpful with early insomnia (insomnia at the earlier hours of sleep) |

Titrate to effect, as per pharmaceutical guidelines (CPS in Canada)

- As a patient’s condition deteriorates, certain non-pharmacological interventions will become less realistic (e.g. exercise). Energy conservation and restoration will become of utmost importance.

- Ensure that If the appropriate supports are in place to assist with activities of daily living and that nursing care is available as needed.

- Drowsiness may increase as the end of life approaches due to disease progression (and/or medications). Some families and patients may even prefer increased sleepiness if it makes the patient more comfortable.

- Hepatic encephalopathy therapy can be continued during this time if the patient is able to swallow.

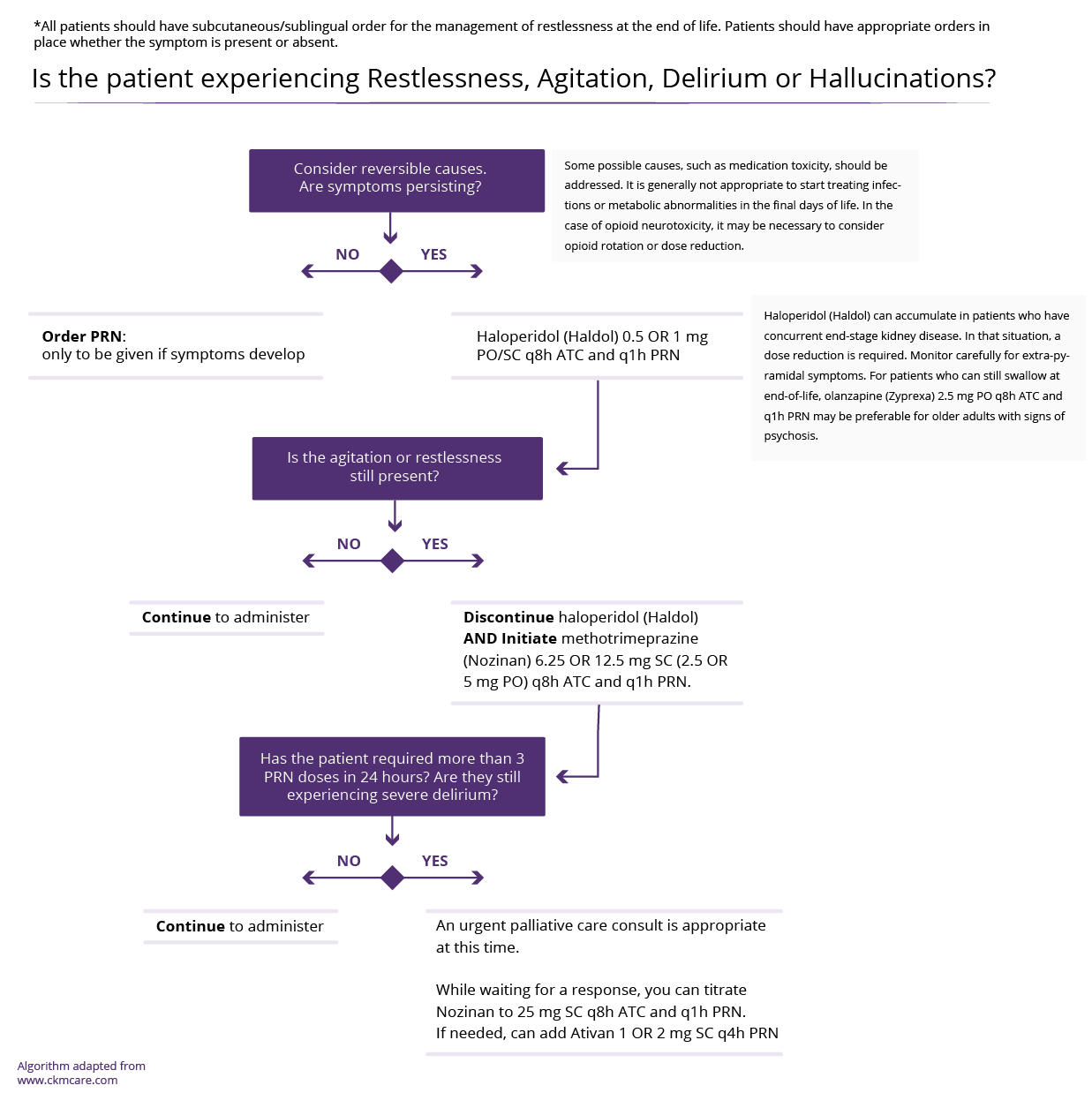

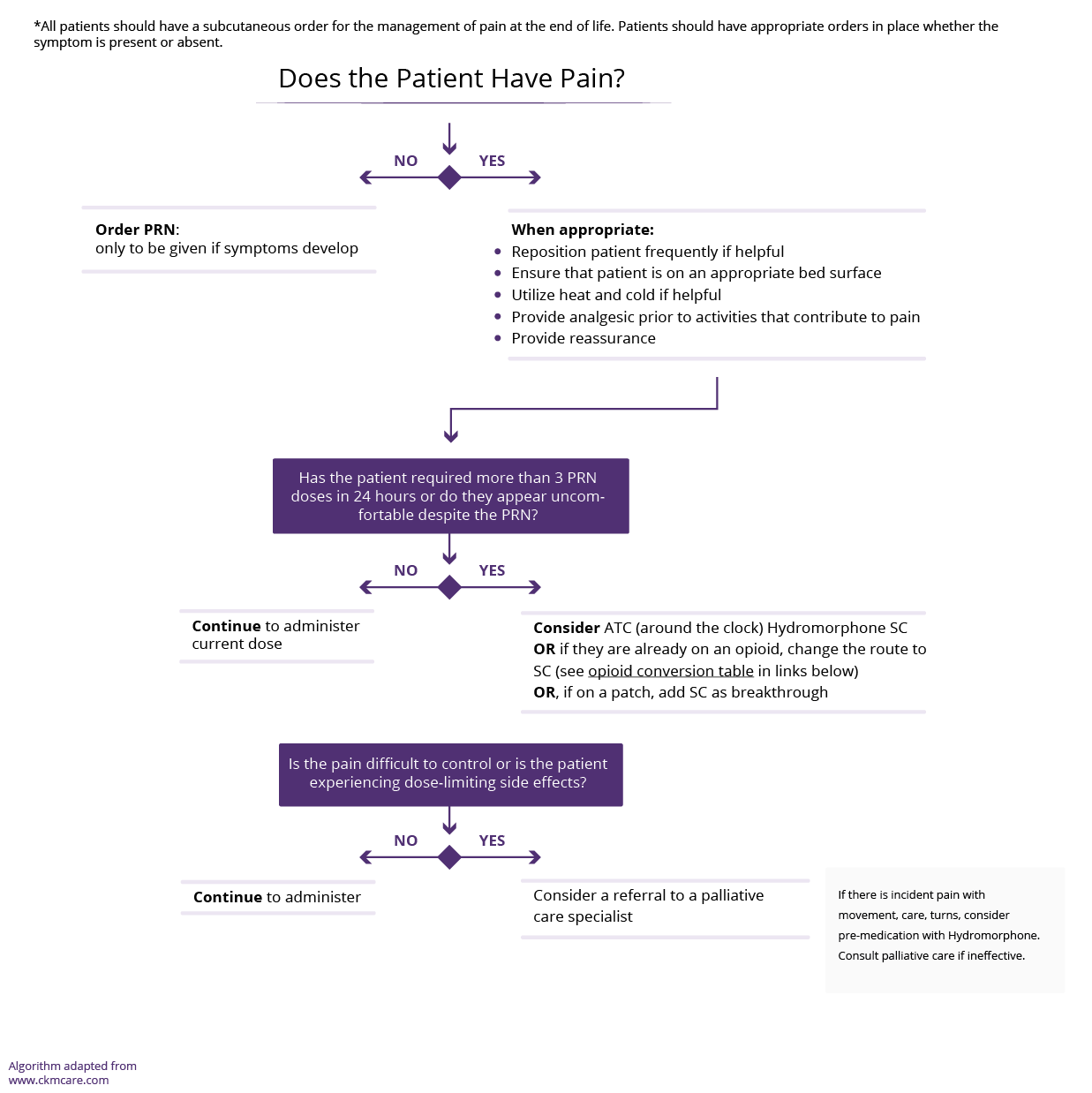

- The following medications can be considered if the first line pharmacological therapies are ineffective.

| Medication: | Recommended Dose | Additional information |

|---|---|---|

|

Mirtazapine (Remeron) |

7.5 mg PO qhs |

For use at End of Life For use at End of Life |

|

Trazadone |

25mg PO qhs Max dose 100mg PO qhs |

For use at End of Life-Can be helpful in mid-late insomnia |

|

Quetiapine |

12.5-25mg PO qhs |

For use at End of Life QT prolongation, hepatic metabolism |

This section was adapted from content using the following evidence based resources in combination with expert consensus. The presented information is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of physicians or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient’s care.

Authors (Alphabetical): Amanda Brisebois, Sarah Burton-Macleod, Ingrid DeKock , Martin Labrie, Noush Mirhosseini, Mino Mitri, Sara Montagnese, Kinjal Patel, Aynharan Sinnarajah, Puneeta Tandon

Thank you to pharmacists Omer Ghutmy and Meghan Mior for their help with reviewing these pages.

Helpful links:

- Hepatic Encephalopathy:http://cirrhosiscare.ca/treatment-provider/hepatic-encephalopathy-hcp/

- Sleep-wake patterns in patients with cirrhosis: All you need to know on a single sheet. A simple sleep questionnaire for clinical use: https://europepmc.org/article/med/19664835

- Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS): https://epworthsleepinessscale.com/about-the-ess/

References:

- Bajaj JS, Elwood M, Ainger T et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy improves patient and caregiver-reported outcomes in cirrhosis. Clin Transl Gastronenterol 2017;8(7):e108. PMID: 28749453.

- Formentin C, Garrido M, Montagnese S et al. Assessment and Management of Sleep Disturbance in Cirrhsois. Current Hepatology Reports 2018 17:52-69. PMID: 29876197.

- Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991; 14(6):540-5. PMID: 1798888.

- Montagnese S et al. Sleep-wake patterns in patients with cirrhosis: All you need to know on a single sheet. A simple sleep questionnaire for clinical use. J Hepatol 2009 51:690-695. PMID: 19664835.

- Moore C. Evaluation and management of insomnia, muscle cramps, fatigue, and itching in cirrhotic patients. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2016 Jan 29;7(1):5-7. doi: 10.1002/cld.516. PMID: 31041016; PMCID: PMC6490243.

- Newton JL, Jones DE. Managing systemic symptoms in chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;56 Suppl 1:S46-55. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60006-3. PMID: 22300465.

- Sharma MK, Kainth S et al. Effects of zolpidem on sleep parameters in patients with cirrhosis and sleep disturbances: A randomized, placebo-controled trial. Clin Mol Hepatol 2019 Jun; 25(2):199-209. PMID: 30856689.

Last reviewed July 3, 2024